In healthcare, communication is an integral part of our working day. Communication is verbal and non-verbal.

Non verbal communication1

This includes:

- Personal space

- Touch

- Eye contact

- Facial expressions

- Gestures

- Postures

In the aged care setting we communicate with residents, families, doctors, direct colleagues, and other healthcare professionals including wound care nurses, practice nurses, and palliative care nurses.

There are many barriers to effective communication including:

- Fear of unleashing strong emotions, upsetting the resident

- Fear of causing more harm than good

- Fear of being asked unanswerable questions such as “why me?”

- Fear of saying the wrong thing, or the discussion not being part of the role

- There is no point talking about things when we have no answers

Verbal Communication Skills

Verbal communication includes language, words and paralanguage (tone of voice, pitch and clarity or rate).

Questions can be asked in a variety of ways, and may be broad, open, directive, closed multiple or leading.

Open questions are useful when you need more than a yes or no answer, and encourages the resident to talk freely.

For example:

- “What do you understand about your illness?”

- “How do you feel about going back to the clinic today?”

- What sorts of things are important to you as you approach the end of your life?”

Other verbal behaviours facilitating communication include:

- Listening: This is an active skill that requires giving full attention.

- Silences: Allows both parties time to think and process what is been said. Provides as space for the resident to say more.

- Encouragement: This indicates you have heard the resident: “Yes”, “mmm”, “That is interesting, please go on”.

- Acknowledgement: Letting the person know not only are they being listened to but they have been heard

- Picking up on verbal cues: “It’s difficult”, “I don’t know how I feel”, “He told me I have cancer”.

- Non-verbal cues such as crying, sighing, frowning, or a look of despair.

- Reflection: The technique of reflection encourages people to talk about a problem they may want to discuss further “So you have been feeling down lately”

- Clarification: Ensuring the resident has understood. “So what do you mean by that?”

- Exploration: This enables more detail to be drawn out…”Can you tell me exactly what is worrying you?”

- Empathy: Demonstrates an understanding of what you have heard “It sounds as if you are feeling low”.

- Summary: This provides a verbal summary of a discussion

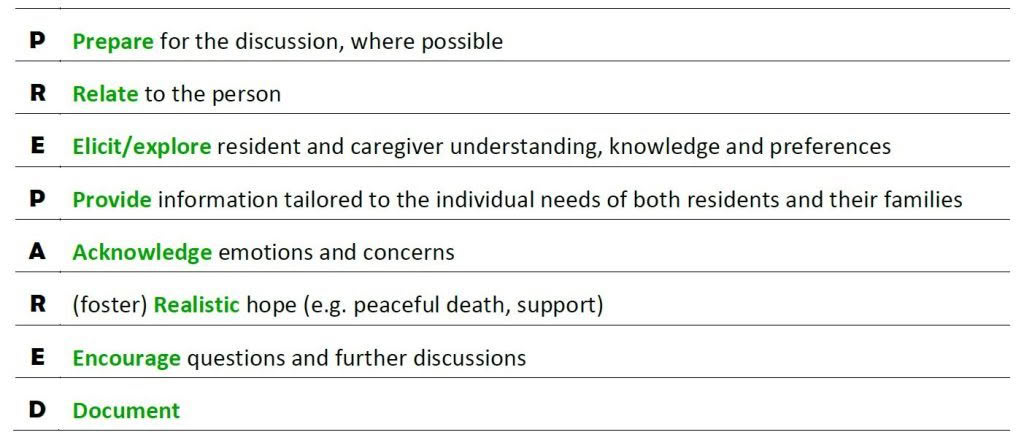

The following table shows key strategies that can be used when communicating with a person with a life-limiting illness and their family.

Use the acronym PREPARED2

⇒ Prepare for the discussion:

- ensure facts about the patient’s clinical circumstances are correct

- try to ensure privacy and uninterrupted time for discussion. Ask if there is anyone else they would like to be present

- mentally prepare

⇒ Relate to the person:

- develop a rapport, show empathy, compassion e.g “This has been a tough time for you and your family...”

- broach the topic in a culturally appropriate and sensitive manner

- make eye contact (if culturally appropriate), sit close to the patient, use appropriate body language, allow silence and time for the patient to express feelings.

⇒ Elicit patient & caregiver understanding, knowledge and preferences:

- identify the reason for this consultation and elicit the patient’s expectations

- clarify the patient’s or caregiver’s understanding of their situation. consider cultural and contextual factors influencing information preferences. How much do they want to know?

⇒ Provide information:

- tailored to the individual needs of both patients and their families

- offer to discuss what to expect, in a sensitive manner, giving the patient the option not to discuss it

- give information in small chunks at the person’s pace

- use clear, jargon-free, understandable language

- explain the uncertainty, limitations and unreliability of prognostic and end-of-life information e.g. "I know that often people expect doctors to know what is going to happen, but in truth we can often only take educated guesses and can often be quite wrong about what the future holds, and especially how long it is. What we can be sure about is ... and what we don’t know for sure is ..."

- try to ensure consistency of information

- use the words 'death' and 'dying' where appropriate.

⇒ Acknowledge emotions & concerns:

- explore and acknowledge the patient’s and caregiver’s fears, concerns and their emotional reaction to the discussion e.g. “What worries you most about…?” or "What is your biggest concern at the moment?”

- initiate/ engage in conversations about what may happen in the future e.g. “Do you have any questions or other concerns?”

- respond to the patient’s or caregiver’s distress regarding the discussion, where applicable.

⇒ Realistic hope:

- be honest without being blunt

- do not give misleading or false information to try to positively influence a patient’s hope

- reassure the patient that support, treatments and resources are available to control pain and other symptoms

- explore and facilitate realistic goals and wishes and ways of coping on a day-to-day basis

⇒ Encourage questions:

- encourage questions and information clarification; be prepared to repeat explanations

- check understanding of what has been discussed

e.g. "We’ve spoken about an awful lot just now. It might be useful to summarize what we’ve said”

⇒ Document:

- write a summary in the medical record of what has been discussed

- speak or write to other key health care providers involved in the patient’s care. As a minimum, this should include the resident’s general practitioner.

1. Communication (2016). Downloaded: http://www.advancecareplanning.org.nz/healthcare/resources/#tab_tab1

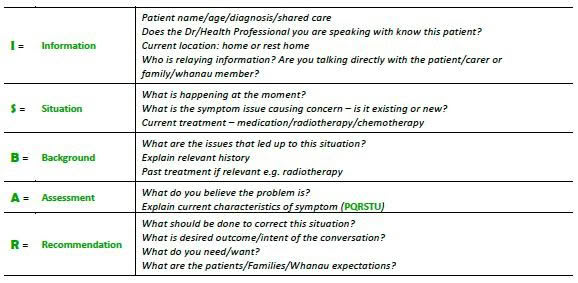

ISBAR

The ISBAR tool is a framework that represents a standardised approach to communication, and can be used in any situation. It is particularly useful when communicating with health professionals.

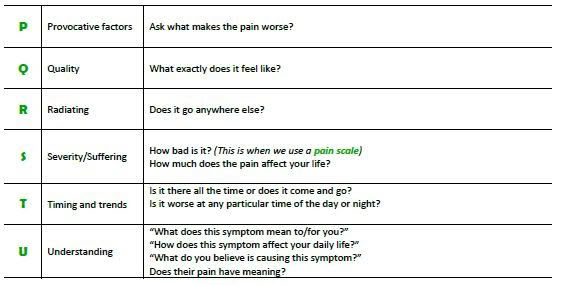

The assessment part of the ISBAR tool considers the following: